African American Military Service - the Irony of Freedom

Defending an idea of the American dream that doesn't include you.

AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNICATORS NEWS ARTICLE

Thomas Y. Lynch

11/11/20257 min read

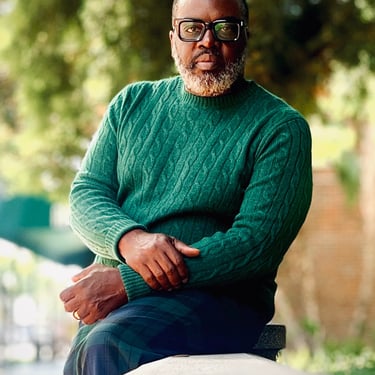

My father served in the Army, in the 1970s, my grandfather served in the Army in World War I, my family has a lot of veterans in its ranks and serving America is a major part of how I was raised. I’ve been watching the headlines and hearing the whispers about efforts by the current administration to sideline, de-emphasize, or remove the stories of notable African American service members from historical collections. As a Black man, I can’t let that pass without doing my part. The record is clear: Black military service is not a footnote to America’s story; it is a thread that runs through the fabric of the nation itself. These men fought for a country that often refused them dignity, yet their courage, discipline, and sacrifice helped build and defend the United States. What follows is a reflection on five groups whose service shaped this country in profound ways, alongside the lives of decorated or emblematic figures whose stories are worth knowing.

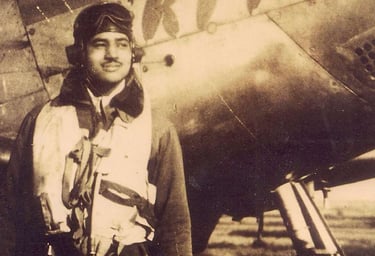

My Father, Thomas Alexander (pictured right), US Army - Okinawa Japan

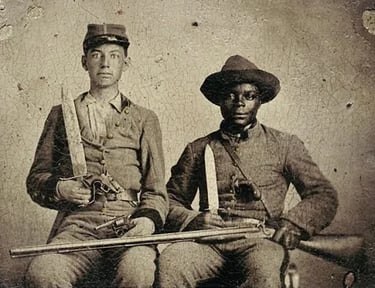

Despite the uniform and weapons, Silas never ‘served’ the Confederacy or fought as a soldier in the Confederate army. Like thousands of other Black men, Silas went to war, attached to his enslaver, as a body servant or what I call camp slave.

Black Confederate soldiers

This is something that always perplexed me, until I started to research their role in the war - let’s just say it was complex. The question of Black Confederate soldiers is one of the most debated topics in Civil War history. The Confederacy was founded to preserve slavery and did not officially authorize Black enlistment as soldiers until March 1865, near the war’s end, and even then, there is little evidence of formally mustered Black combat units seeing battle under Confederate arms. That said, thousands of enslaved and free Black men were compelled to labor for Confederate armies as teamsters, cooks, body servants, laborers, and fortification builders. Their presence in Confederate military spaces is undeniable, but their status was not that of recognized soldiers with rights or equal pay.

A figure often cited in this context is Silas Chandler, an enslaved man who accompanied his enslaver, a Confederate soldier, into the war. Photographs of Chandler in uniform have been misused to suggest that he served as a Confederate soldier. The historical record indicates he was enslaved and forced to serve as a body servant and laborer, not a enlisted soldier. His story is significant precisely because it reminds us to read images and claims critically and to honor the truth about coercion, resistance, and the limits placed on Black agency within the Confederate war machine.

Born into slavery, Carney escaped to freedom and joined the 54th, the Union Army's first official black regiment recruited in the north.

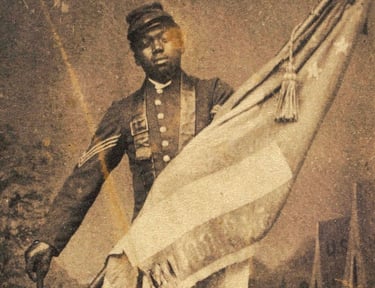

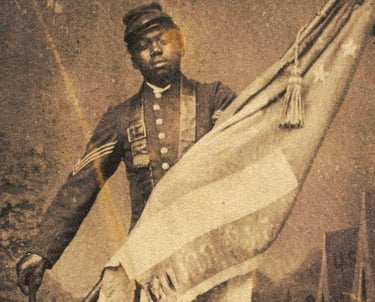

African American soldiers in the United States Colored Troops

When the Union began formally recruiting Black soldiers after the Emancipation Proclamation, nearly 180,000 men enlisted in the USCT, with another 20,000 serving in the Navy. These soldiers fought in battles from Fort Wagner to Petersburg, bore heavy casualties, and helped tip the balance of the war. Their service transformed the conflict into a revolution for freedom and citizenship. The USCT’s contributions were strategic and moral. They bolstered Union numbers, guarded supply lines, assaulted fortifications, and proved beyond doubt that Black men would fight and die for the Union and for their own liberation.

Sergeant William H. Carney of the 54th Massachusetts, though technically a state regiment, is the iconic figure here. At the assault on Fort Wagner in 1863, Carney seized the fallen American flag and carried it forward despite being gravely wounded. He reportedly said, “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground.” Carney later received the Medal of Honor, the first African American to be so recognized. His courage became a living argument for Black citizenship.

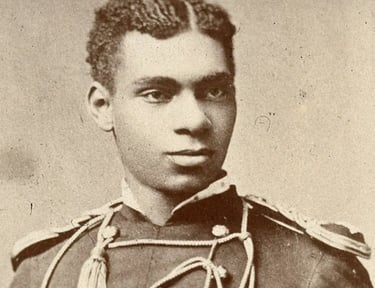

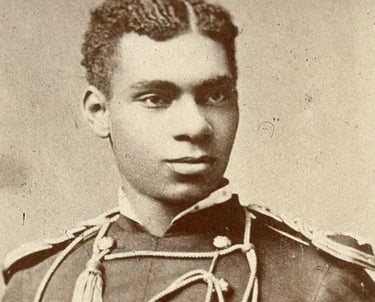

Henry Flipper was a former slave who achieved a significant milestone by becoming the first African American to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1877.

Buffalo Soldiers

After the Civil War, Congress created segregated Black regiments in the Regular Army, most famously the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Native communities called them Buffalo Soldiers, a name that stuck. They patrolled the western frontier, built roads and telegraph lines, protected national parks, and fought in the Indian Wars, the Spanish American War, and the Philippine American War. Their story is complicated, because their service coincided with and contributed to U.S. expansion that often harmed Indigenous peoples. Yet their professionalism and valor were unquestioned.

One of the most decorated was Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper, the first Black graduate of West Point, who served with the 10th Cavalry. Despite enduring racism and a contested court martial that ended his Army career, Flipper’s legacy as a pioneering officer was later acknowledged when he received a posthumous pardon. The Buffalo Soldiers’ discipline helped establish the U.S. Army’s reach, while their excellence made a case for Black leadership within institutions that tried to keep them out.

Brigadier General Charles E. McGee (1919 - 2022) was apioneering African American fighter pilot with the Tuskegee Airmenwho became an Air Force legend, known for flying more combat missions across three wars (World War II, Korea, and Vietnam) than any other Air Force pilot in history.

Tuskegee Airmen

In World War II, the idea that Black pilots could not fly, fight, or lead was widespread and institutionalized. The Tuskegee program in Alabama shattered it. The 99th Fighter Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group flew combat missions over North Africa, Italy, and central Europe. They escorted bombers, strafed ground targets, and earned a reputation for precision and courage. Their contributions were tactical and symbolic. They helped win air superiority in key theaters and struck a blow against the myth of Black inferiority in one of the most technical branches of wartime service.

One emblematic figure is Colonel Charles E. McGee, who flew 409 combat missions across three wars and embodied sustained excellence over a lifetime. Another is Captain Roscoe C. Brown Jr., a distinguished pilot who shot down a German Me 262 jet—no small feat. The airmen’s success helped lay groundwork for desegregation in the armed forces and the eventual dismantling of some barriers in American life.

Sergeant Henry Johnson (c. 1892–1929) was a U.S. Army soldier in the all-Black 369th Infantry Regiment ("Harlem Hellfighters") who became a national hero for his extraordinary valor in World War I, though he was denied proper U.S. military recognition for decades due to systemic racism.

Harlem Hellfighters

The 369th Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters, served with distinction in World War I. Denied the chance to fight alongside white American units, they were assigned to the French Army, which welcomed them and supplied them with French equipment. They spent more days in combat than almost any other American unit, fought fiercely in the Champagne and Meuse Argonne sectors, and returned home to a hero’s parade along Lenox Avenue. Their music and culture also helped carry jazz to Europe.

Private Henry Johnson stands as one of the war’s greatest heroes. During a night raid, Johnson fought off a German patrol with rifle, grenades, and a bolo knife to save a wounded comrade, Needham Roberts. He suffered multiple wounds and was long denied full recognition by his own government. Decades later, he received the Medal of Honor. Johnson’s story speaks to courage under fire and the long fight for acknowledgment.

Our contributions will never fade

These histories do not exist outside the nation’s story. They are the nation’s story. From coerced labor under the Confederacy and the transformational service of the USCT, to the professional might of the Buffalo Soldiers, the skybreaking achievements of the Tuskegee Airmen, and the dogged valor of the Harlem Hellfighters, these men pushed America closer to its ideals. They fought enemies abroad and racism at home. They risked their lives for a country that often met them with segregation, suspicion, and silence. Yet their work safeguarded the nation, advanced the cause of freedom, and opened doors for generations to come.

As a communications professional, my career is rooted in amplifying truth—and I would be remiss to allow the erasure of the history that African Americans contributed to building this country, especially through service in uniform. So when anyone suggests erasing or diminishing these chapters, I say that’s not just an attack on Black history. It’s an attack on American history. These contributions make up what America is. Their story is tied to our shared past and present. Even through racism and rejection, these men fought for the chance to be free not only in the world but back home, where too many were not accepted. Remembering them is not an act of nostalgia. It is an act of truth-telling and a commitment to the America they helped make possible. In honoring their courage, we protect the integrity of our national narrative—and we reaffirm the values they defended with their lives.

“How well we communicate is not determined by how well we say things but how well we are understood.”