Gordon Parks: Photography = Storytelling

Three Foundational Practices That Still Define Visual Storytelling

GOVERNMENT COMMUNICATIONS AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNICATORS

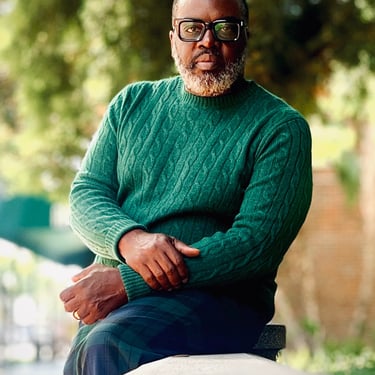

Thomas Y. Lynch

10/19/20255 min read

When I design anything for my job, business or personal portfolio, it’s about presentation and image. I’m so corporate, I like clean lines, sufficient white space, pop colors and a stunning photo that conveys the emotion of the subject matter. Because my foundation is rooted in photography, I have several photographers that I follow and some that I truly admire. Gordon Parks is one that I mimic on occasion.

Gordon Parks wasn't just a photographer; he was a visual communicator who understood that images could change minds, shift policies, and humanize complex social issues. His approach to photography established practices that remain essential to how government communications professionals tell stories today.

Let's examine three foundational elements of Parks' work and why they matter now more than ever.

1. Color: Strategic Emotional Communication

Gordon Parks was a master of color capturing it, and wielding it as a communication tool. When he shot fashion spreads for Life magazine, he used vibrant, saturated colors to celebrate Black beauty and elegance in publications that had rarely featured it. When documenting poverty and injustice, he often employed muted, somber tones that conveyed dignity within hardship without sensationalizing suffering. Parks understood what today's government communicators know instinctively: color isn't decoration but in its truest form, it is messaging.

Personal Example:

I work for an organization that centers on tackling LA’s homeless crisis. One characteristic that is at the foundation of the work I do is bringing dignity and credibility to the organization. As an artist I often create in the realm of contrasts. I recently covered a homeless encampment located in the desert. I choose to use vibrant colors to convey the situation. Homelessness is not easy to live through, but I wanted to show the people living in the encampment through the lens of hope and new opportunity. Not by downplaying their temporary living conditions, but enhancing it through color. I was still committed to the authenticity of the story.

Example: Vibrant colors can uplift and show hope at homeless encampment.

How it shapes us today: Government visual communications now routinely consider color psychology in brand guidelines, and cultural sensitivity. We've learned from Parks that color must be intentional, not arbitrary.

2. Composition: Framing Dignity and Context

Parks' compositional choices were revolutionary because they centered human dignity while providing social context. Look at his iconic 1942 photograph "American Gothic”: a Black cleaning woman standing before an American flag, holding a broom and mop. The composition deliberately echoes Grant Wood's painting, but Parks' framing tells a different American story. He positions his subject centrally, meeting her at eye level, giving her the same compositional respect typically reserved for portraits of power. This compositional philosophy, centering subjects with dignity while revealing systemic context is now standard practice in government communications.

Parks taught us that composition answers the question: Whose perspective are we privileging?His low angles elevated subjects society marginalized. His environmental portraits provided context without overwhelming the human story. His careful framing ensured backgrounds informed rather than distracted. His composition just simply worked, not pretentious but appropriate.

Personal Example:

I was covering the Maternal Health Program from the office of Diversion &Reentry. We were highlighting a success story. The client invited us into her home, and my job was capture her everyday environment as she told her story. What stood out to me was her daughter and how she is the beneficiary of a mother who learned from mistakes and set her child up for success. I tried to capture that with my images.

Example: Photography can show human dignity and compassion rewriting stigma.

How it shapes us today: This compositional philosophy, centering subjects with dignity while revealing systemic context is now standard practice in communications. Most government photography guidelines now emphasize authentic representation, diverse perspectives, and compositions that respect the subject’s position. We've moved away from "poverty porn" or "hero shots" Parks' balanced approach—showing challenges without stripping dignity, celebrating achievements without erasing context.

3. Cultural Relevance: Photography as Social Documentation

Perhaps Parks' most enduring contribution was his insistence that photography must engage with cultural reality. Whether documenting the Fontenelle family in Harlem, covering the civil rights movement, or profiling emerging artists, Parks created images that mattered because they reflected the urgent social questions of his time. He didn't just photograph abstract concepts; he photographed people experiencing the reality of their environment.

Personal Example:

One thing that I learned when I was working for San Bernardino Probation Department was that officers are people too. The department’s commitment to diversity was absolute. Through photography I was able to document the everyday preparation of law-enforcement. The bigger picture to me was capturing officers from every segment of the population to protect their community.

Example: Photography can humanize and shape public perceptions.

How it shapes us today: This commitment to cultural relevance is now the cornerstone of effective government communications. If there is a window to show a different perspective, good communicators tell the story that contradicts the unpopular narrative.

Parks proved that culturally relevant photography requires more than technical skill—it demands understanding your subjects' lives, respecting their stories, and recognizing how individual experiences reflect systemic realities. He spent time in communities before photographing them. He built relationships. He understood that authentic visual storytelling requires genuine engagement.

The Legacy Lives On

Gordon Parks didn't just take beautiful photographs, he established a visual language for institutional storytelling that prioritizes humanity, dignity, and truth. His practices set the standard in publications from Life magazine to government reports, from news media to nonprofit communications. His legacy remains relevant today because the fundamental challenge hasn't changed: How do we use photography to tell our organizations' stories in ways that inform, inspire, and create understanding?

Every time a government agency publishes an annual report featuring real people rather than stock images, that's Parks' influence. Every time a public health campaign uses photography that reflects community diversity, that's his legacy. Every time we choose images that humanize policy rather than abstract it, we're following the path he cleared. His camera was never neutral, and neither are ours. The question is whether we'll use our visual storytelling with the same intentionality, dignity, and cultural awareness that defined his revolutionary work. That's not just good photography, it’s good governance.

Thomas Y. Lynch

The Legendary Gordon Parks

Capturing the essence of African Americans

“How well we communicate is not determined by how well we say things but how well we are understood.”